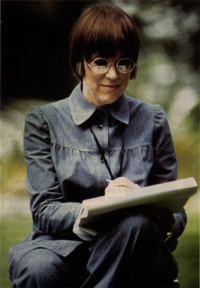

Translator of Italian versions of Kubrick's films, Aragno was Kubrick's close friend and coworker from the 1960s on. The photo at right shows the writer with an original copy of Eyes Wide Shut, the last film he translated, and a personal letter from Kubrick in which the director dismisses criticism of the Italian version of A Clockwork Orange: "Dear Riccardo, The story about the Clockwork Orange dubbing is a complete nonsense. I have always used the Italian dub as an example of how good a dubbing can be. My best to you and Mario. Stanley" (April 10, 1996, published in Ciak July 1999).

Translator of Italian versions of Kubrick's films, Aragno was Kubrick's close friend and coworker from the 1960s on. The photo at right shows the writer with an original copy of Eyes Wide Shut, the last film he translated, and a personal letter from Kubrick in which the director dismisses criticism of the Italian version of A Clockwork Orange: "Dear Riccardo, The story about the Clockwork Orange dubbing is a complete nonsense. I have always used the Italian dub as an example of how good a dubbing can be. My best to you and Mario. Stanley" (April 10, 1996, published in Ciak July 1999).

|

Stanley Kubrick's Italian friend

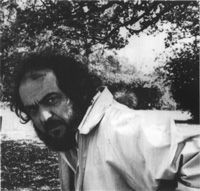

"An isolated ogre? A neurotic, distant man? He was the happiest guy I've ever met! In his private life he was always joking around." Riccardo Aragno is moved. He was Kubrick's italian friend, a journalist and screenwriter, and he worked on all the Italian versions of Kubrick's films. Aragno is 84. His friendship with Kubrick began in 1961. "We met in London, in Peter Sellers' house, for whom I wrote The millionairess, a movie with Sofia Loren directed by Asquith. The day after we met, he called me at home: 'It's Kubrick, we spoke yesterday at dinner. What are you doing for breakfast?' And so our friendship was born. And we've been faithful friends now for over 30 years. We spent last Christmas together, and he promised me I could translate his last film, Eyes Wide Shut. He wanted me to find an Italian title for it." What was the basis of your friendship? Why he was such a lonely person? What kind of jokes did he tell? Did Kubrick become English? Or did he remain American? Why didn't he go back? Corriere della Sera, 8 Marzo 1999 |

|

Kubrick up close

by Claudio Masenza The Private Life and Work of a Genius, Told by His Italian Friend and Colleague Stanley Kubrick and Riccardo Aragno first met in '61 at Peter Sellers' house warming party in the London countryside. Sellers was making Lolita with Kubrick and had spent the previous year acting alongside Sophia Loren in Anthony Asquith's The Millionairess, which Aragno adapted from a comedy written by George Bernard Shaw. Both foreigners in England, Aragno had been a film critic for the BBC for a some years, during which time Kubrick had made a name for himself with The Killing and Paths of Glory but only Spartacus, the least personal of his films, had been a box office success. The director from the Bronx was 34 years old and fifteen years younger than the intellectual from Torino who would be in charge of the Italian translation and dubbing of his last five films. A costume party at Kubrick's house at the end of the '80s, with balloons. On the left Jan Harlan with his arm around his wife. Next to them, Anja Kubrick and her partner. Anja was born in 1959 and is the older of the two daughters the director had with his third wife Christiane. Following in the photo are Christiane, Stanley, and Katharina K. Hobbs, the daughter that Christiane had with her first husband, Werner Bruhns. "I was born in the age of radio and had known Sellers for years because we'd made the mythic radio program Goon Show together, which he produced. Stanley Kubrick was a big fan of Sellers because, as I later learned, he was intrigued by bizarre types. But everyone loved Peter. Even Princess Margaret, even though he often embarrassed her. Once, at dinner at her house, I had to tell him not to smoke marijuana: the house was full of police officers. That first evening Kubrick was depressed and spoke to me about the dangers of an imminent atomic war. He was certain it would begin due to a stupid error. We spoke about it at length. And he confessed to me that he wanted to by an island in the Pacific to save himself. Three years later Dr. Strangelove was released. Maybe that night, while our friendship was being born, he decided to exorcise his fears by satirizing them on screen. The next day he called me and asked me to breakfast. Our regular breakfasts continued for about thirty years. He went out all the time; he was never a recluse, but he was always poorly dressed and no one ever recognized him." "I quickly became his confidant. In the late afternoon he would call me and invite me to dinner at his place; I always made pasta for him. He loved spaghetti alla puttanesca. Then, after A Clockwork Orange, he was given 50% of the earnings of his films. And when he understood that he would become rich he told me, 'Now the danger is wanting two pairs of shoes.' He wasn't fixed on money, but to protect himself and his family from the media, he bought a huge home in the country enclosed by a high fence. The décor reflected his passion for austerity, but the house was full of cinematographic equipment. There was even a projection room, and on Saturdays, after our regular lunch, we would go back to the house to watch new films. Distributors always sent them to him to ask his opinion. Often, mid-movie, he would propose heading to the kitchen for coffee. And his wife and our friend Milena Canonero would be watching with us and would shout towards the kitchen at us, 'Come back, its' not bad!' But to see a new Petri or Fellini he would run to the theater. He was bored, though, with Visconti's Death in Venice. Many directors wanted to meet him and in those last years he spoke often on the phone with Pollack and Spielberg. I remember, though, that once John Franhenheimer was nearby in London and asked to meet him. But no, Stanley didn't want to lose time with people he considered mediocre. He was instead become friends with Stanley Donen. It was at that time that we were assembling research for a film about Napoleon and the two Stanleys always place Battles, playing out the Battle of Waterloo. And Kubrick won. Always. We worked for two years on Napoleon. Then Metro read the screenplay and said no. It would have cost too much and they were sure that Americans didn't care at all about Napoleon." Another nice photo taken by Aragno at the party at Kubrick's house: from left to right, Anya and her partner, Jan Harlan, Stanley, Christiane and their second daughter Vivian, born in 1960. "He often wanted me on the sets of his films. And I was always interested in watching him at work. The beginning of 2001: A Space Odyssey was filmed with the Front Projection system. They were photographs taken in the desert and projected in MGM's studio theater behind dancers playing as monkeys. And he told me how the civilization was born with the discovery of war." "I began to translate his screenplays into Italian with A Clockwork Orange. He asked me because it was difficult to translate the language of Anthony Burgess, a modest imitator of Joyce, who had created the novel on which Stanley based his film. I worked with Mario Maldesi, who was the adaptor and director of dubbing, and Stanley, who didn't speak Italian, completely trusted us." "A Clockwork Orange was invited to the Venice Film Festival and for the premier, Stanley sent Milena Canonero, the film's costume designer, to substitute the projection equipment there with that of his own projection room: with him nothing could be left to chance. When he was filming Barry Lyndon I worked through 50 seventeenth century operas to find one aria to use in the film. He decided that it needed a specific, romantic music, so I suggested my friend Nino Rota. They worked out a contract immediately and Rota arrived. I took him to meet Stanley and then left them alone. An hour later Rota called me in tears. Kubrick had made him listen to a piece by Schumann and said, 'I want this.' Mediation was useless and they dissolved the contract." "He rarely told actors what he wanted. A little explanation was enough for them to find the right expression. He was sure of his eye and ready to redo a scene even sixty times. Wasting film didn"t bother him. He bought tons of it, always from the same batch. He didn't have deadlines given that he was in charge of his own work. He would wait. But not everyone could meet the standards of James Mason and Peter Sellers. He was always kind but became very nervous around actors. They irritated him, especially those who considered themselves particularly talented. But he thought that bad moods on the set didn't matter, what mattered was what came out on the negative." "He was an atheist Jew who threw Christmas parties. But I didn't go to the last one; I was sick. He told Milena Canonero that he wanted Maldesi and me to work on the Italian version of Eyes Wide Shut. And after Christmas I received the script and a tape of the film with the sequences that could create problems blacked out. I've know now that the question of censuring has been resolved, but I can't say more. I will translate the script and Maldesi will do the dubbing. As always we recorded the auditions for the main roles so that Sanley could listen and decide. Even for Nicole Kidman and Tom Cruise, who had set voiceovers, we were able to work with complete freedom but this time he didn't make it in time to choose. A Roman friend called me around 5:30pm on March 7 to tell me that he had learned of Kubrick's death on the evening news. I couldn't speak until after 9:00" "Then, in the confusion of the moment, I understood that the evening before he had gone to the garage where he had his editing room and where he worked for years, often alone, on his films. The next day the found him there, on the ground. Only now have I begun to understand what I've lost. But I prefer to think about what I had for all these years!" Ciak, July 1999 |

Aragno wrote, close to Kubrick's death, the book Kubrick: Storia di un'amicizia (published by Schena Editore in October 1999) where he describes thirty years with the director, between breakfasts, dinners in the kitchen surrounded by Stanley's labradors, discussions about the movie business, etc. On the back of the book Aragno writes:

Aragno wrote, close to Kubrick's death, the book Kubrick: Storia di un'amicizia (published by Schena Editore in October 1999) where he describes thirty years with the director, between breakfasts, dinners in the kitchen surrounded by Stanley's labradors, discussions about the movie business, etc. On the back of the book Aragno writes:

In Hollywood films were born in studios... Stanley's idea was different: like the painter's one, the sculptor's one, the poet's one, the writer's one, the musician's one... We used an english term for this idea - a bit seriously and a bit comically - "a Cottage Industry".

The book is dedicated to Christiane.

|

Kubrick: a Story of Friendship [excerpts]

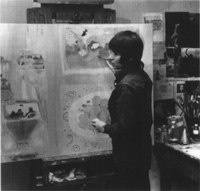

by Riccardo Aragno One evening, in the long grassland of the house in Elstree, owned by Kubrick, Stanley directed the camera towards the couple of labradors that were the actual landlords. After lunch or dinner [at Elstree and after at St. Albans] we used to watch movies. Stanley and me, we were the operators. Interested in every scientific thing, Kubrick plans his films with a military strategy. The plans that Stanley Kubrick the producer planned for Stanley Kubrick the director were extraordinary. Actors that worked with Kubrick and that knew him very scarcely, are often shocked because they are forgotten. They are used to work with directors that play for them, that give long and complex psychological explanation of the characters, or with directors that want rhetorical or theatrical performances. There are still actors with theatrical experiences that confuse a studio with a stage. [...] Once, chatting about photography with new tools that a salesman showed us, Stanley observed that cameras for movies have the same problems than cameras for photos. There are two possibilities: snap or pose. Either you plan places, lights, effects, or you take the right moment, hoping that the destiny gives you a powerful image. We were both enthusiasts for computers, cameras, radios, recorder, amplifiers, microphones, magnetic records, vinyl records, photocopiers, phones with recorders and the possibility to communicate with three or four people simultaneously. But there were other interests too: recipes of Italian food, French cheeses, American and Chinese and Indian foods. [...] And jazz too. [...]

But of course the most important interests were photography and cinema. We liked the variety of focuses, from the "50" with assorted brightness to the more complicated wide-angle lens. We used very much "135" by Nikon for portrait and we arrived with pleasure to the "180" by Angenleux on the Leica and other tools. Until their last day together, Stanley and Christiane have been sincerely loving to each other. The intellectual and sentimental feeling of that couple was the great secret of Stanley and few people understood this. They were a combination of existences. Their thoughts were harmonized in a way that can be rarely seen in a couple. Going to Kubrick's house was, every day, a show of familiar life spent sincerely. I remember Christiane painting "the green" of England, hot-colored works, essential, that show the deep and sentimental relation between man and nature. I remember Stanley solacing his daughter Vivian, sad because she saw a cat killing a bird. "This is nature, honey" said the father to the girl. "We'll have to get another bird, Vivian." Kubrick: Storia di un'Amicizia, Schena Editore, 1999 |